Our Mobility Future May be More Autonomous, but Will it be More Equitable?

MZ Strategies, LLC is working in numerous regions to advance partnership between advocates, private developers, financers, housing intermediaries and public-sector agencies to ensure that all families -- regardless of race, income-level, gender, or ability -- are provided equal access to housing that is affordable. New research by the National Low-Income Housing Coalition reminds us yet again that not a single state in American has enough rental units for minimum-wage earning renters.

As bleak as the housing outlook is, I find myself pondering these challenges within the larger context of community change especially related to mobility. New technologies, shifting driving preferences, and changing demographics are profoundly disrupting how people move around our cities, and how future transportation investments should be planned and financed. Whether as investor or operator, the private sector is playing a growing role in American mobility systems. The big debate raging at the moment is not whether, but when autonomous vehicles may become the norm and what that will mean for our cities.

Transportation innovation, particularly as it relates to an autonomous vehicle future, should not be considered in isolation of housing policy or social equity. Our nation has a dismal track record when it comes to the impact of new infrastructure technologies on low-income households and communities of color. Freeways and urban renewal programs decimated African American communities. Jim Crow laws started and were personified by racist streetcar and bus policies. An astounding number of the nation’s airports and freight facilities neighbor low-income communities and contribute to serious environmental health risks for those populations. Broadband infrastructure has largely side-stepped poor urban and rural communities.

Mariia Zimmerman, Principal of MZ Strategies, LLC moderates the plenary panel on Federal, State and Local Policies to support Equity and Sustainability at SUMC18.

Transit investment limps along in most places and expensive new investments in rail too often primarily serve “choice” suburban riders at the expense of service improvements to those relying on transit to reach jobs, schools, doctors and family. Transit-oriented development projects, especially when geared towards higher income Baby Boomers or Millennials can displace long-term residents and small businesses in some communities.

Yet, transportation is fundamental to allowing people to exist and hopefully thrive in their regions and communities. Whether by foot, by wheel, or by rail, transportation gets us where we need and want to go. Yet because of past inequities, decades of disinvestment or explicit racial bias, not all communities have equal access to convenient, affordable and safe transportation.

In their 2012 study of employment access by transit in America’s 100 largest metropolitan areas, the Brookings Institution found that typical job is accessible to only about 27% of a region’s workforce by transit in 90 minutes or less. For low-income workers, especially those living in the suburbs, job access is even more problematic. “About one-quarter of jobs in low- and middle-skill industries are accessible via transit within 90 minutes for the typical metropolitan commuter, compared to one-third of jobs in high-skill industries.”

How can investments in bike sharing and other shared mobility technologies benefit low-income riders, rather than just be seen as a symbol of gentrification? (Photo: MZimmerman)

If technology promises the opportunity to radically transform, and we hope improve mobility, we cannot afford to take a myopic view of the challenges that it needs to solve. Beyond an obsession with “efficiency” we need new mobility services, tech tools and policies that advance and address equity goals both for riders and those working in the industry. Yet I continue to see a substantial disconnect in my work with communities. Equity advocates are focused on the disparities and threats facing their communities today. No one is talking about the possible future impacts of autonomous vehicles.

When shared mobility enters the discussion, it is viewed with mistrust and antagonism that a proposed bike share station or new bike lanes will displace existing community residents . These concerns require community collaboration to address and overcome. We must also recognize and mitigate racially-motivated transportation decisions made in previous decades. But we can’t limit equity engagement only to addressing past or current challenges, we must look ahead at the future that is being planned right now by automotive and technology companies in partnership with many in the public sector.

New transportation technology debates talk about customer-focused transportation and efficiency, but for whom? The transportation technology revolution is shifting who operates and owns data, technology, curb space and our streets. It’s also transforming how we access, pay for, and view mobility – all of which can have a positive or negative social equity impact far beyond just those who take Uber.

Earlier this week I attended the National Shared Use Mobility Summit (#SUMC18). Over 600 people came together in Chicago from across the globe to talk about ride hailing services (TNCs), dockless bike sharing, electric and autonomous shared vehicles. Innovative pilots are being tested in places as diverse as Vermont, Tucson and Seattle to improve mobility for underserved populations including those with disabilities, youth and rural communities.

At the heart of many discussions was how and whether public transportation can co-exist with shared use mobility, particularly if we define shared use merely as a more convenient form of cab service where one car is transporting one person. On the one hand we have research from Regina Clewlow and Gouri Shankar Mishra at UC Davis, and by transit agencies in several individual cities, that finds a significant loss in transit ridership from commuters who appear to be switching to services like Uber and Lyft. On the other hand, we have research by the American Public Transportation Association that finds numerous causes behind the national drop in transit ridership beyond just the rise of TNCs. Of note, gentrification occurring in transit-rich, walkable neighborhoods and the resulting displacement of low-income, transit users to areas that are not well served by transit is also a factor.

Recent research by the Shared Use Mobility Center (SUMC) finds no clear correlation between agencies that saw losses in transit riders versus cities with growth in TNCs. Rather TNC growth happens at times of day or for types of trips where transit may not be the best option. As a woman traveling in unfamiliar neighborhoods at night for work, I call up Lyft on my phone rather than walk several blocks to catch transit because it feels safer and is quicker. I’m not alone. Additional research by SUMC finds that TNCs are an important compliment to transit in providing first and last mile connections, and to enabling people to live without owning a car.

Yet, most shared use mobility conversations this week at the Summit reinforced a potentially false narrative. It’s easy to believe in a room of predominately white, well-educated transportation and technology geeks (regardless of whether we work in public or private sectors) that the new mobility paradigm promised by autonomous vehicles and shared mobility will improve life for everyone. Transit agencies, and many equity advocates rightly fear that in the rush to embrace new tech tools we once again lose sight of larger mobility needs. In this sense, as Jarrett Walker reminds us, it’s pretty hard to beat bikes or transit, especially when designed to maximize their performance.

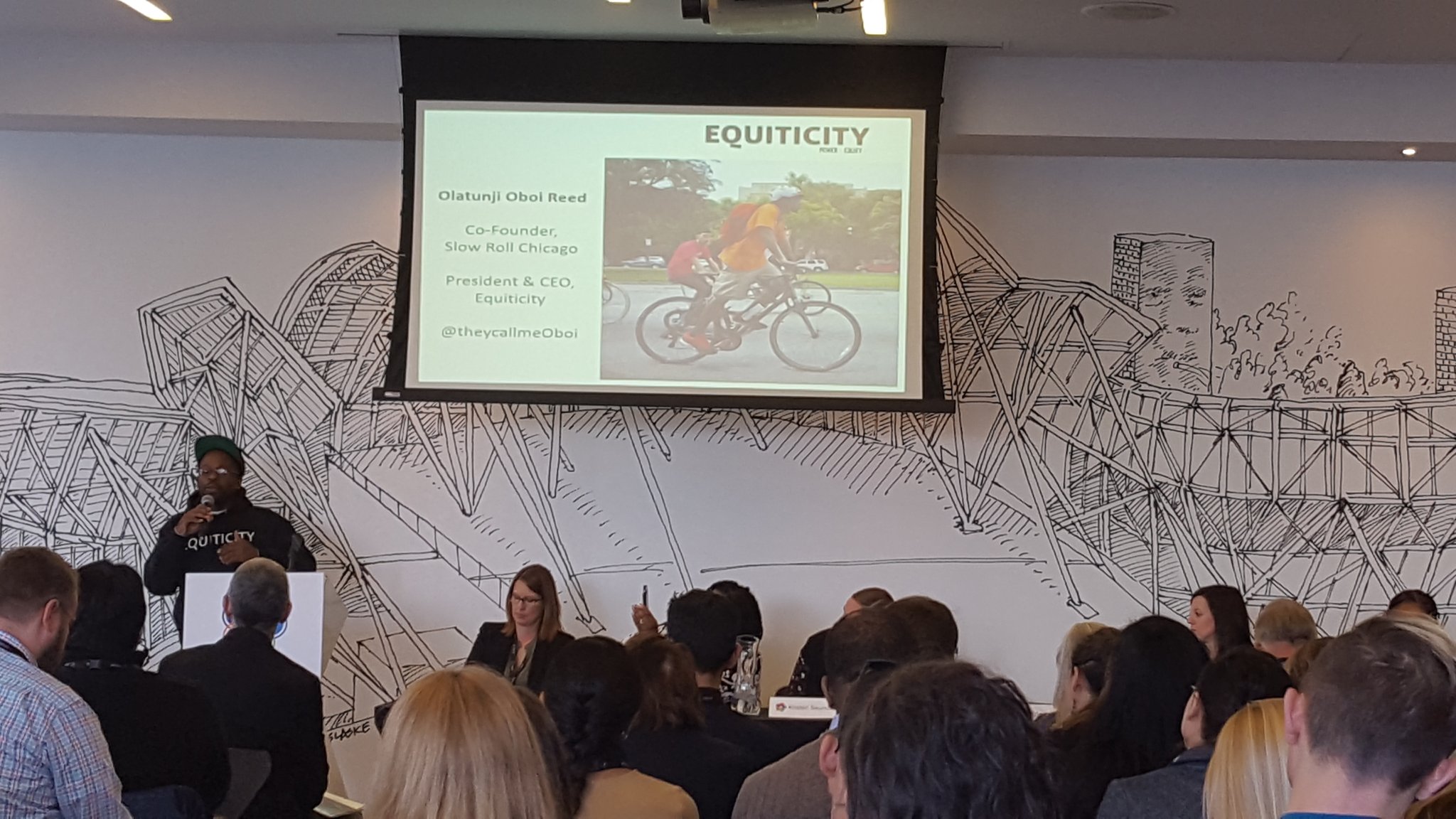

We must bridge transportation innovation, shared mobility and equity conversations. Among those leading this charge is Oboi Reed, Founder of EquitiCity in Chicago whose mission is simple yet bold: “Equiticity is a racial equity movement working to improve the lives of Black, Brown and Indigenous people of color by harnessing our collective power through programming and advocating for racial equity, increased mobility and racial justice across the U.S.”

Oboi Reed of EquitiCity speaking at SUMC18 reminds us that mobility is transformative, and key to racial equity. (Photo: MZimmerman, 2018)

At the heart of his work is empowering community leaders to be the voice and the vanguard of change. Oboi is an eloquent and passionate champion for authentic, operational equity as a mobility outcome with community ownership at its heart. This requires investment from neighborhoods and partnership initiated by neighborhoods, rather than a top down process where new investment is done to neighborhoods.

Serious questions remain about who stands to benefit the most, and for whom are new technologies being designed. Perhaps even more importantly, who is designing them. Are we doomed to repeat the past where government agencies or private industries push solutions on communities? Or, can we finally learn that their ultimate success in transforming mobility requires authentic community voice in the design, the planning, and the implementation of new transportation models? Achieving the latter won’t happen just with good intentions. Safeguarding existing federal planning requirements that ensure community engagement is critical, but also only a first step.

We need to prioritize mobility options that improve market failures and mobility deficits faced by those who are disabled, cannot afford an automobile, or are too young or old to drive. We must not plan for a shared mobility future that threatens the vibrancy of our towns, cities and walkable neighborhoods or undercuts workforce development goals and viable transit service. In the strive to innovate we must test new approaches and models that strengthen community ownership and operations.

Working with numerous international partner organizations, Robin Chase – an early and steadfast thought leader in new mobility has proposed a set of Shared Mobility Principles for Livable Cities. They provide an excellent framework and include a specific commitment to promote equity: “Physical, digital, and financial access to shared transport services are valuable public goods and need thoughtful design to ensure use is possible and affordable by all ages, genders, incomes, and abilities.”

So, will autonomous vehicles be a panacea or another pandemic for low-income households and communities of color? Only time will tell, but so far, most discussions of a brave, new autonomous future fail to happen within broader discussions of economic and racial disparities that exist today, much less are they being considered within a broader regional context of housing and land use policy.

We all need to recognize the interconnections between transportation, housing and equity. We must not shy away from addressing and reconciling the complicated history of urban housing and transportation choices. Rather, we must work together to ensure that America’s future mobility systems don’t exacerbate inequality. New thinking, new partners, and new technologies create unprecedented opportunity.

To that aim, I offer the following quote sent out last summer after the tragic events in Charlottesville by Ford Foundation President Darren Walker, to serve as a touchstone and challenge to all of us working on these issues: ‘At the same time, I recall James Baldwin’s words during the heights of the civil rights movement in 1965: “History … does not refer merely ... to the past ... History is literally present in all that we do.” And so I am mindful that just like the leaders who came before us, we are caught between the history from which we emerge and the history to which we aspire.’