Infrastructure and Housing: Local Dreams and Federal Illusions

I’ve spent most of this past month, in fact way too much time this past month, in discussions about a potential Trump administration infrastructure proposal. Will they or won’t they? How much detail will it actually include? Is the leaked 6-page memo real? How do we reconcile his rhetoric with the real cuts that have been proposed in his first budget? Will it be DOA in Congress?

It’s easy to get distracted by this all, and no doubt when we finally see something there will be a flurry of analysis and comment making. But until then, let’s not forget what we know. Folks at the Brookings Institution, Transportation for America, and the Transport Politic have done a great job tracking the bevy of proposed budget cuts, federal delays of transit projects, and regressive surface transportation positions the administration has taken in its first year. And while it’s easy and exciting for some of us to talk transit, roads, and bridges, let’s not forget that housing is also a major part of America’s infrastructure. For a guy who has made and lost billions as a housing developer and landlord, it seems Mr. Trump conveniently forgets this.

Expanding affordable housing opportunities in suburban communities is significantly at risk given actions by the Trump Administration to suspend Fair Housing efforts, cut funding to existing programs and from the recently passed federal tax reform. (Photo: A new affordable housing project in Hopkins, MN near a proposed transit station, M. Zimmerman, 2017)

January started with the announcement by the US Department of Housing and Urban Development that it was suspending, at least until 2020, the recently-adopted Affirmatively Furthering Fair Housing (AFFH) rule which requires communities to complete a Fair Housing Assessment, and moth balling its Fair Housing assessment tools currently being used by hundreds of communities across the country. As noted by Jeff Siskin at Curbed, this is the second Obama-era anti-segregation policy HUD has tried to impede (the first being a failed attempt to delay federally-subsidized renters more choice in where they live). All of this serves as a depressing reminder that 50 years after passage of the Fair Housing Act we appear further rather than closer to realizing the dream of safe, secure housing for everyone. Today, over 70 percent of the country’s lowest-income households who are working a full-time, year-round job face severe housing burdens.

The AFFH rule is important for many reasons, including actual implementation of the 1968 Fair Housing Act. It requires that communities receiving HUD funding review their housing policies as they relate to segregation and submit a plan, called an Assessment of Fair Housing (AFH), that identifies strategies (investments, policies, zoning) it will take to combat it. Failure to submit an AFH could result in a loss of HUD dollars.

The suspension of the Fair Housing rule (finalized by the Obama administration in 2015), comes on top of changes to the federal tax code passed in late December that some experts estimate will reduce production of new affordable housing units by at least 235,000 homes over the next decade. This comes at a time when nearly every region of the country faces a shortage of housing affordable to people at a range of moderate to lower incomes. In our large metro areas the problems are especially acute with even those earning six-figure salaries spending over half their monthly income on housing. For those living in poverty, housing stability has become a myth as so painfully portrayed by Mathew Desmond in last year’s Pulitzer Prize winning “Evicted.” Low-income renters, in particular, are being displaced and gentrification of neighborhoods that for the last half-century were home to people of color is forcing out small business owners, residents and wholesale cultures. Regional economic, health and educational disparities are at an all time high, even in those metropolitan areas where recovery from the recession is now yielding financial growth.

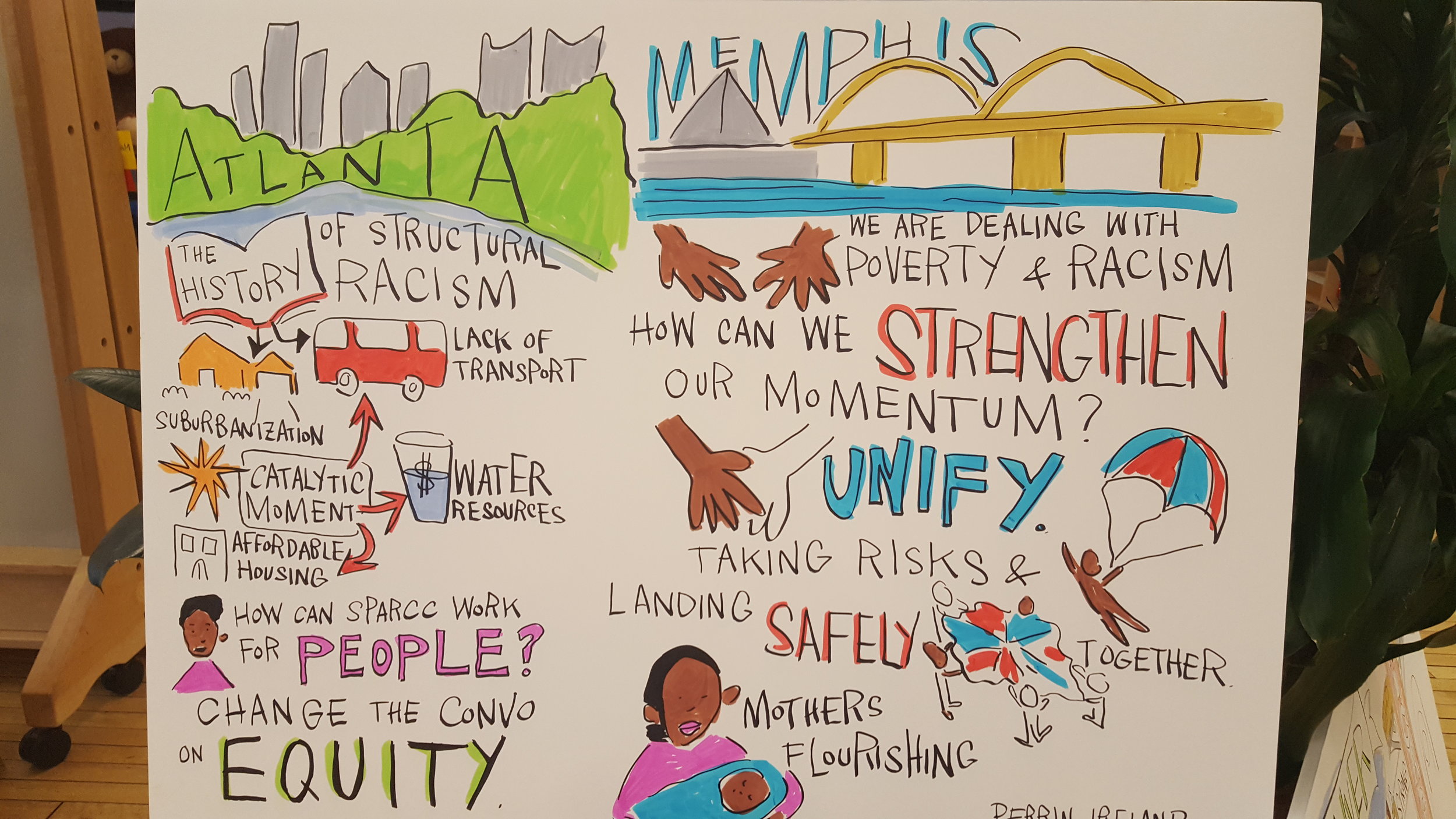

Regions like Atlanta and Memphis, in support with the SPARCC initiative, are advancing opportunities to create more inclusive, opportunity-rich communities that put racial equity at the forefront of economic and community development (Photo: M Zimmerman, 2017)

The fact that it took nearly 50 years for the federal government to issue a rule to implement the Fair Housing Act speaks volumes about the formidable challenge our country faces on issues of race and affordable housing. Almost regardless of political party or the size of a community, opposition to adequate housing is strong and often the loudest from those cities with the wealthiest and whitest populations.

In the words of my friend Nathaniel Smith at the Partnership for Southern Equity, we must recognize that "Policy is really the reflection of the values of our public officials. To change policy, we need to change our values, through conversations bringing multi-class, multi-racial coalitions together, to care about each other."

Throughout my career, first working on transit and later on housing, I’ve heard the persistent fear of residents that improving transit or providing housing for low-income people will ruin the community, make homeowners less safe, or reduce property values. Racism and classism often underlies this opposition, either explicitly or implicitly. Even when provided with facts that disprove these fears, the voice of opposition is persistent and local elected officials often find it hard to row against a populist NIMBY tide. It’s precisely because of the difficulty at the local level to address such issues that the Fair Housing Act was created in 1968. It’s also why, in my years working at HUD, local officials quietly expressed their appreciation of federal requirements that provide cover to do things they knew were necessary but may be politically unpopular.

Currently my own community is grappling with how to address Richmond’s long-standing affordable housing needs that for centuries have been explicitly shaped by racism. We cannot go back and change time, but we can recognize that zoning and funding decisions must change. This is easier said than done, especially when money is tight, and fears remain that taking action may cost the city residents, employers, or general funds. A proposal to require developers to provide a modest amount of affordable units in projects supported by city funds or property has so far received a skeptical response from City Council members. Yet, the region’s housing market is booming and the City lacks affordable housing money. This is not a challenge unique to Richmond.

Adding to the complexity of addressing affordable housing needs within any community is the fact that public agencies are not well structured, nor adequately funded, to address the growing crisis of affordability that threatens those living in poverty and a growing number of middle class households. Housing agencies often focus only on administering housing subsidies and may lack a department or municipal directive that looks at housing more strategically.

Most regional agencies do not have a responsibility for housing and so coordination across jurisdictions is difficult. In some places, regional planning agencies and metropolitan planning agencies (MPOs) are stepping up to play a more active role in housing and equity issues. They assume correctly that things like traffic congestion, highway expansion and transit ridership are directly impacted by where people live. They recognize that low-income workers need better mobility options to access regional jobs. And they understand that the combined costs of housing and transportation are the two single largest costs for most households. California’s state climate legislation and housing policies now require regional plans that link housing and transportation. Yet, the majority of America’s MPOs and transit agencies still resist engaging on regional housing issues – especially when it comes to fair housing – because they take a very myopic view of transportation viewing it as an outcome not an input to how well a region functions, and to what degree households have access to economic opportunity.

The decision by this administration to suspend the Fair Housing rule is a cruel one. We cannot pretend that racial segregation does not exist. Public schools are more segregated today than 40 years ago. Suburban poverty and racial segregation are also greater. There are a number of causes including exclusionary zoning policies and market forces --- precisely things that the AFFH rule asks jurisdictions to consider … not solve. We can do better, and I was honored to work in the last administration where HUD leadership believed in the ability of this generation of America’s community leaders to finally tackle Fair Housing. Then Deputy Secretary of HUD, Ron Sims, set a national challenge that a person’s zip code not determine their life expectancy, or their income, or their education attainment.

Back in 2010, we naively believed in a post-racial America, and felt ourselves following in the footsteps of civil rights leaders who came before us and dreamed of a better and more inclusive America. We knew this work would not be easy and so HUD under Secretaries Shaun Donovan and Julian Castro committed to developing new tools, technical assistance and a set of principles that could finally move fair housing from being a reactive litigious debate to a proactive, inclusive planning discussion. HUD leadership recognized that housing problems cannot be solved only with housing solutions. People make decisions about where to live based on schools, jobs, quality of life and access to opportunity. Unequal access to these opportunities combined with a lack of affordable housing sentences low-income seniors, children, and workers to an endless cycle of poverty.

For those regions and cities that engaged in the process of looking comprehensively at the impediments not only to fair housing but also access to opportunity, the new federal data tools and HUD directive changed local conversations. I witnessed this first hand in many regions in which I work. In Minnesota’s Twin Cities, for instance, an analysis of impediments and racially-concentrated areas of poverty supported work by regional partners and the Metropolitan Council to undertake the first regional housing policy in 40 years. In places such as Austin, TX, Seattle, WA and Portland, OR, and Rhode Island, local jurisdictions came together to develop a regional analysis and consolidated plan for working together to expand housing options.

In its decision to suspend the Fair Housing rule, HUD cites the fact that 35% of those who submitted an AFH since 2015 fell short in their first submission. This is a cop-out and fails to recognize that the majority did comply. There is also nothing to prevent HUD from continuing to refine its analytics and provide technical assistance to more communities with the rule still in place. However, this administration instead continues to propose significant cuts to the HUD budget. Most housing experts anticipate forthcoming legislation that will likely cut housing assistance to low-income residents by changing rent structures and imposing punitive requirements.

Local communities, knowing that they are needing to do more robust analysis and strengthen partnerships beyond usual suspects, are stepping up to the challenge. Putting these discussions in limbo – as the suspension of HUD’s AFFH rule does -- is a failure of leadership. If we believe in “putting your money where your mouth is,” this administration’s infrastructure commitment is profoundly lacking. There is no benign failure to act, but rather a series of very intentional efforts to undermine long-overdue progress to correct decades of racial segregation. In the face of a crisis in housing affordability, this administration is making a series of cuts that collectively reduce private and public affordable housing finance and weaken housing production. Proposed restructuring of Fannie Mae and the Community Reinvestment Act could put corporate interests even more highly over that of low-income households, first time homeowners, and seniors living on fixed incomes. And so, in our excitement over what may possibly happen with a new infrastructure proposal, let’s not lose sight of what is happening right now in the world of housing infrastructure.