Engage Local. Putting Community at the Center of Public Engagement

Public engagement. Two words with good intentions but that cause consternation for many. If you are a resident it may cause eye rolls and cynicism as you recall past meetings where the people spoke but it felt that no one listened; or maybe you didn’t even get that far if the meeting was poorly advertised or at a time you were working. If you are a local planner it may fill you with dread as you envision countless nights of public meetings filled with NIMBYs pushing against plans that have been months, if not years, in the making. If you a transportation engineer, you may bemoan the time it adds to a project yet a necessary box to check in order to meet federal planning requirements. If you are an elected official, you may question the usefulness or reliability of tapping precious city funds to pay consultants to lead a public engagement process that only reaches a few hundred people in a community of thousands.

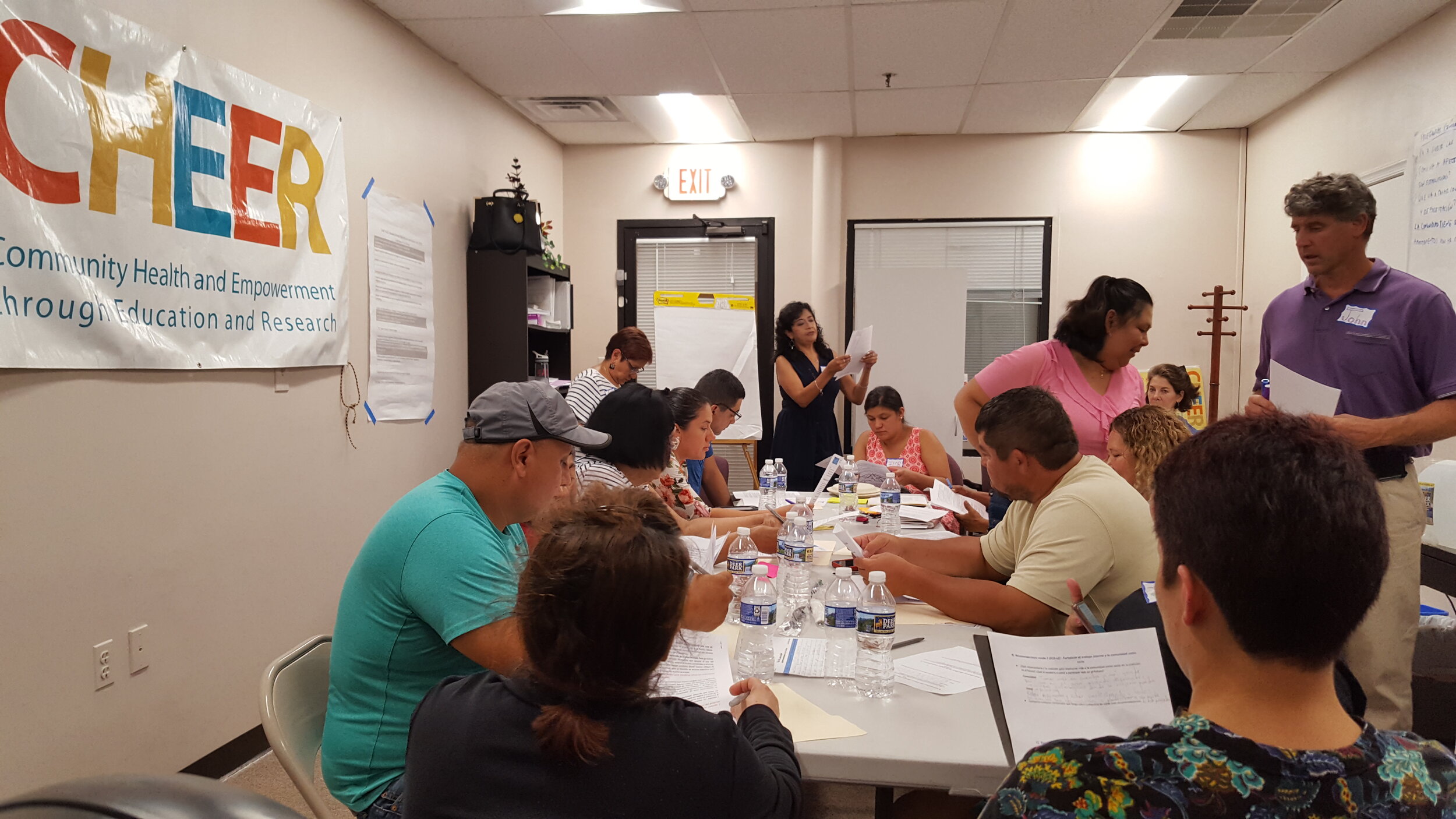

This summer, MZ Strategies and Public Engagement Associates partnered with CHEER and CASA de Maryland to engage local residents in crafting a Housing Action Plan for the Purple Line corridor. This work was funded by Enterprise Community Partners and included conducting a focus group entirely in Spanish. The Purple Line Coalition committed to this approach as a way to get more input from renters and LatinX households who may be most impacted by housing market changes.

Several cities across the country such as Durham, NC; Minneapolis, MN; Oakland, CA and Seattle, WA, are actively working to change this dynamic by turning public engagement on its head. Rather than starting with a draft plan, policy or project to which the public sector seeks comment and hopefully endorsement from a broad set of stakeholders, some jurisdictions are stepping back and putting community at the start of the process to shape solutions and define problems. This approach, often referred to as equitable community engagement, recognizes local residents and community-based organizations as assets that can be resourced to play an active partnership role. Public agencies are advancing this work through adopting equitable engagement principles, creating Equitable Engagement Blueprint documents, and even more importantly committing public funds and redesigning how engagement contracts are being written, how staff are being trained, and how local organizations are being compensated for their time and partnership.

The commitment to equitable engagement entails two major fundamental shifts by the public sector. The first, is a recognition that people are a community’s greatest asset. Like other assets, finding ways to leverage and grow its wealth yield tremendous results. For instance, small investments to fund locally-based neighborhood organizations to help lead engagement and outreach efforts builds both their own capacity but also utilizes local knowledge and relationships that enhance the public sector’s ability to connect with customers, constituents, and users of the systems they are working to create. This approach acknowledges something very fundamental: public policies, programs and investments impact the trajectory of people’s lives. The people crafting these policies, programs and investments may never meet the people that are impacted nor directly feel the impacts themselves. People closest to the challenges can also be those closest to the solutions if given the right resources and opportunities.

Recently I heard author and Robin Hood CEO, Wes Moore articulate this well for both those working in public, and non-profit parts of community development: “How is the end user involved in our work? We aren’t there to save them. Our job is to ensure they are empowered and own the solutions.”

The second shift is a recognition that just like in many other areas, equity and equality are not synonymous. Equality means giving everyone the same bite at the apple. Equity recognizes that not everyone may be able to take that bite so additional accommodations may be necessary. In the world of public engagement, meetings and outreach are often implicitly designed for those who

Illustrating Equity vs. Equality - Image by the Interaction Institute for Social Change | Artist: Angus Maguire”

a) can easily travel to attend a meeting which may or may not be accessible without a car and often are held in the afternoon (when they may be working) or in the early evening (when they may also be working, or coming home from work and trying to make dinner, help kids with homework, etc);

b) are fluent in English;

c) who perceive their self-interests to be at risk (ie homeowners) or are really geeky about the topic (yes, I’m talking to my biking friends and train foamers); and

d) have access to the internet or on social media as these are both used with increased frequency to share information.

You may have other implicit (or explicit) barriers that come to mind, but even with just this list of four we can see why many people in communities may be unable to participate. The common result is that those with the most time and resources to participate are the ones who do, especially if they do not like what is being proposed. People of color, especially non-English speakers or new immigrants, low-income residents many of whom work multiple jobs during the day and evening, as well as renters are often under-represented. Equitable public engagement acknowledges these barriers and under-representation and commits resources and intentional practices to ensure greater and more diverse participation by all members of a community.

This approach has been much on my mind and increasingly influencing the work and practice at MZ Strategies. During my time at HUD when I had the privilege of serving as Deputy Director for the Office of Sustainable Housing and Communities we required our planning grantees to dedicate a portion of their funds to equitable engagement practices. This yielded some stunning results that are still bearing fruit. I’m reminded of this when I see the work happening in a variety of regions:

· In Atlanta, the City worked with local partners to create the “Atlanta Community Engagement Playbook” that offers a step-by-step set of actionable practices and checklists that can be used to create more open, inclusive and fun engagement practices.

· The City of Minneapolis created an Office of Neighborhood and Community Relations that works with Public Works to engage affected residents in prioritizing sidewalk and street improvements within racially-concentrated poverty neighborhoods.

· Local leaders in King County, Washington adopted an Equity Impact Review (EIR) process that has been in use for several years and merges empirical (quantitative) data with community engagement findings (qualitative) to inform planning, decision-making and implementation of actions that affect equity in King County. The County’s Community Engagement Guide operationalizes equity impacts in the review of county infrastructure projects.

A new white paper released by the Strong, Prosperous and Resilient Communities Challenge (SPARCC) spotlights numerous local efforts to advance equitable engagement practices. Download at www.sparcchub.org

This week the Strong, Prosperous and Resilient Communities (SPARCC) initiative released a white paper written by MZ Strategies (with the input of numerous equitable engagement practitioners from across the country and within the SPARCC network) that shares these and other equitable engagement practices. This work was inspired by the leading-edge efforts happening to redefine equitable engagement. It also responded to requests by SPARCC partners for more tangible examples of how different public agencies are approaching this work. How can contracts or other forms of compensation be created for those with needed local expertise? How are equitable engagement practices being embedded within planning and budgeting processes? The good news is there are far more examples that I uncovered than I was able to put in the paper, and equitable engagement is not just something for the public sector. The bad news is that still not enough agencies or organizations are utilizing this approach. But I am hopeful.

In my own community of Richmond, Virginia public engagement practice is shifting. Just like the local foods movement has shown that procuring from local farmers, bakers, and brewers creates a better tasting, healthier product. Procuring locally-grown community engagement partners also creates a better end product and leaves the entire community healthier. The Richmond Memorial Health Foundation has steadily been investing in local community capacity through funding efforts like the City Builders program staffed by 6PIC and RVA Groundworks to engage youth and local residents in one of the city’s long-time African American neighborhoods where economic and health disparities are pronounced. The neighborhood is beginning to gentrify and City Builders is a locally-based program working to equip residents with the tools needed to engage in larger city planning processes. With other grants, the City Builders and 6PIC team are partnering with VCU, the City of Richmond, and Richmond Public School District to engage local youth in designing strategies to combat eviction, homelessness, and inform the City’s comprehensive plan.

Another powerful example can be found in Virginia Community Voice (another RMHF grantee) where planning and engagement is grounded in local voice and representation. Through it’s RVA Thrives work, storytelling, surveys and interviews with local residents living in the neighborhoods along the Jefferson Davis highway corridor were asked: “what would it look like and take for your community to thrive?” Local residents – a majority of whom are people of color who earn less than the regional area median income -- are in the driver’s seat to design the scope and goals for the corridor. The approach centered on the power of neighbors being able to connect with each other and to allies outside of their community. Residents are equipped with the tools necessary to take greater leadership over decisions affecting their community.

As a consultant who does community engagement, my own eyes have been opened. Whereas in the past I felt comfortable leading engagement efforts in communities that were not my own given my confidence with knowing the subject matter and a sense of self- assuredness; today I realize that is ridiculous. It is not my place to speak for a community nor assume I know what is best for it. My role is to find capable and inspiring local organizations whom I can partner with to share the knowledge that I bring so that local residents, business owners, and community leaders can have the information they need to confidently engage in the decisions that impact their lives. Our success is tied.

I also feel a new responsibility when working with public agencies or other clients to encourage them to think more innovatively. This may involve committing resources to train their own staff and helping connect them to cultural-competency and racial awareness organizations. It may be suggesting meetings held in neighborhoods rather than City Hall, translating materials into languages other than English, and designing meetings to provide child-care, food, and stipends when appropriate. It may be brainstorming ways to sub-grant to local organizations or non-English speaking meeting facilitators. It may be establishing a set of equity principles, and then operationalizing them.

Just as I no longer enjoy a McDonald’s cheeseburger with the same relish that I did before discovering how amazing a farm-to-table burger can be, traditional public engagement methods now fall flat to me after being part of some amazing equitable engagement practices. This is all a long way of saying, I hope you’ll join me to “Engage Local.”